🔴 Website 👉 https://u-s-news.com/

Telegram 👉 https://t.me/usnewscom_channel

The mysterious Denisovans, perhaps the most elusive of all the archaic hominin species, emerged following their divergence from Neanderthals approximately 400,000 years ago. Like Neanderthals, these extinct cousins of modern humans made important contributions to the human genome, which helped shape our evolution and make us what we are today.

But as new research has revealed, the story of the Denisovan genetic exchange with early humans was more complex than previously known.

In a new study just published in the journal Nature Genetics, two scientists affiliated with Trinity College Dublin’s Smurfit Institute of Genetics, lead author Dr. Linda Ongaro and her colleague Dr. Emilia Huerta-Sanchez, reviewed all the existing literature on Denisovan and human interbreeding, and were able to identify three separate periods when Denisovans were breeding with early humans regularly. They also found that the Denisovans had split into two distinct populations at some point, but that both of these had interbred with human ancestors, adding yet another layer of complexity to these interactions.

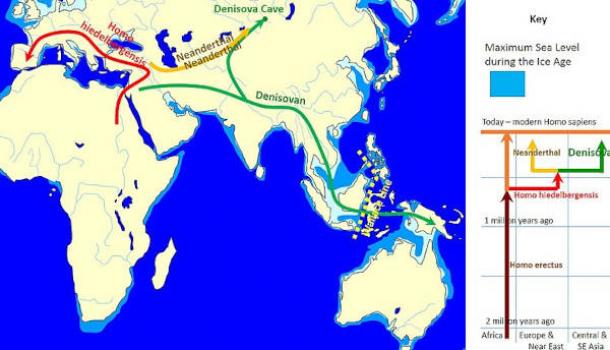

Chart showing migration patterns and evolutionary history of Denisovans (and other ancient hominins). (John D. Croft/CC BY-SA 3.0).

As Dr. Ongaro explained in a Trinity College Dublin press release, genetic experts have been able to figure all of this out through the in-depth study of the human genome.

“By leveraging the surviving Denisovan segments in modern human genomes, scientists have uncovered evidence of at least three past events whereby genes from distinct Denisovan populations made their way into the genetic signatures of modern humans.”

The complex and surprisingly frequent interactions between Denisovans and early humans are intriguing, given the scarce nature of the recovered Denisovan remains (only a few individual bones or pieces of bones and teeth have been found). It is known that the Denisovans first appeared in Eurasia during the Pleistocene epoch, because of these few fossils, but beyond that the genetic fingerprint they left in the human genome is the only real evidence that reveals anything about their existence.

The Denisovans Live On, Inside the Human Genome

Based on all the research Drs. Ongaro and Huerta-Sanchez reviewed, it seems that at their peak of population the Denisovans inhabited an extensive geographic area, extending from the frozen climate of Siberia to the high altitudes of the Tibetan Plateau, and likely to the east and down into Southeast Asia and Oceania as well. The diversity in their range and the climates they inhabited suggests they may have been quite adaptable, and they are known to have passed some of that adaptability along to the human evolutionary line, through interbreeding with early humans and some of their archaic ancestors.

What is known for sure now is that before they all disappeared about 50,000 years ago, there were two distinct Denisovan populations. One of them lived in the Altai Mountains of Siberia (among other places), where the Denisova Cave (the site where most Denisovan fossils have been discovered) is located. The second lived on the Tibetan Plateau and left behind one striking fossil—part of a jawbone with two molars still embedded—in that region’s Baishiya Karst Cave, and they developed separately from the more well-known group that lived in Siberia.

Denisova Cave, located in Altai Mountain region of Siberia. (Демин Алексей Барнаул /.CC BY-SA 4.0.).

Each of these groups left their mark in the human genome, Dr. Ongaro noted.

For example, the Tibetan group had a high level of tolerance to low-oxygen conditions, which would have been common at high altitudes. They passed that along to humans to at least some extent, through the lasting contributions they made to humanity’s collective gene pool. Meanwhile, the Siberian population that endured extreme cold developed a heightened immune response and a more efficient capacity for burning fat for calories, and the Denisovan genes associated with the latter have been found in Inuit populations that survive in the Arctic.

These are just some of the ways that Denisovan DNA has benefited humans. Previous research has found that Denisovan genetic material is most common in Aboriginal Austalians, Papuans, Near Oceanians, Polynesins, Fijians, Eastern Indonesians, and the Aeta people from the Philippines. Anywhere from two to six percent of the DNA of these groups can be traced back to the Denisovans, and it likely confers various benefits that have yet to be discovered.

A Complex Picture of Human Evolution Emerges

While the primary focus of her research was on the Denisovan-human connection, Dr. Ongaro believes this is only one part of a much more complex picture. These interactions actually occurred within the context of a broad and inclusive pattern of archaic hominin interbreeding, she asserts, that saw Denisovans, Neanderthals, early Homo sapiens, and possibly other archaic species exchanging genetic materially quite liberally.

“It’s a common misconception that humans evolved suddenly and neatly from one common ancestor,” she said. “The more we learn, the more we realize interbreeding with different hominins occurred and helped shape the people we are today.”

It is possible that some human populations contain bits and pieces of Denisovan DNA that has yet to be detected. This situation could change with more extensive research into the human genome, but archaeology also has an important role to play in learning more about who the Denisovans were, how they lived, and where and when they would have been most likely to interact with humans.

Denisovan molar recovered from Denisova Cave, Siberia. (Thilo Parg/CC BY-SA 3.0).

“Integrating more genetic data with archaeological information—if we can find more Denisovan fossils—would certainly fill in a few more gaps.” Dr. Ongaro acknowledged.

The spread of Denisovan DNA through various human populations certainly shows they traveled farther than just Siberia and the Tibetan Plateau, and if archaeologists are eventually able to discover more remains in other locations it could go a long way toward solving the mystery of who the Denisovans really were.

Top image: Piece of Denisovan jawbone with two attached molars, recovered from Baishiya Karst Cave on Tibetan Plateau. Source: Dongju Zhang/CC BY-SA 4.0.

By Nathan Falde