🔴 Website 👉 https://u-s-news.com/

Telegram 👉 https://t.me/usnewscom_channel

A fascinating study of the skeletal remains of ancient Egyptian scribes from the third millennium BC has revealed the physical costs of this job. While the type of work they did might seem relatively non-stressful, in fact these men suffered from skeletal damage and degenerative osteoarthritis that affected the joints in many different parts of their bodies, which undoubtedly turned writing into a surprisingly painful profession for many.

In this new study published by Nature, a team of researchers from the Czech Institute of Egyptology in Prague examined the skeletal remains of 69 adult males who lived in ancient Egypt between the years 2,700 and 2,180 BC, during the Old Kingdom period. The skeletons were recovered from a multigenerational elite necropolis unearthed near the village of Abusir, which is adjacent to an ancient pyramid complex.

Cross Profession Study Group

The skeletal remains belonged to men from two different groups: those who had worked as scribes, and those who had not. There were 30 individuals who belonged to the first group, and a close analysis of their remains showed clear anatomical anomalies that were not present in the members of the control group.

“Statistically significant differences between the scribes and the reference group attested a higher incidence of changes in scribes and manifested themselves especially in the occurrence of osteoarthritis of the joints,” the Czech researchers wrote in an article just published in Scientific Reports.

“Our research reveals that remaining in a cross-legged sitting or kneeling position for extended periods, and the repetitive tasks related to writing and the adjusting of the rush pens during scribal activity, caused the extreme overloading of the jaw, neck and shoulder regions.”

Among other things, this proves that scribes were dedicated to their work, and were willing to put up with a lot of discomfort to complete their assignments.

Model of the skull of Nefer—”overseer of the scribes of the crew” and “overseer of the royal document scribes”. Credit: Veronika Dulíková, Czech Institute of Egyptology; data processing and creation of 3D model Vladimír Brůna, Zdeněk Marek, Department of Geoinformatics, UJEP Most. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University

The Scribes of Ancient Egypt: Their Lives and Lifestyles Finally Revealed

The scribes of ancient Egypt were a revered and exalted class. As masters of the written word, which was invented by the Egyptian god Thoth and therefore considered sacred, scribes were treated as political or religious royalty, enjoying high salaries and many different forms of privilege.

“Officials with scribal skills belonged to the elite of the time and formed the backbone of the state administration,” Egyptologist and study co-author Veronika Dulíková told Live Science. “They were therefore important for the functioning and management of the whole country.”

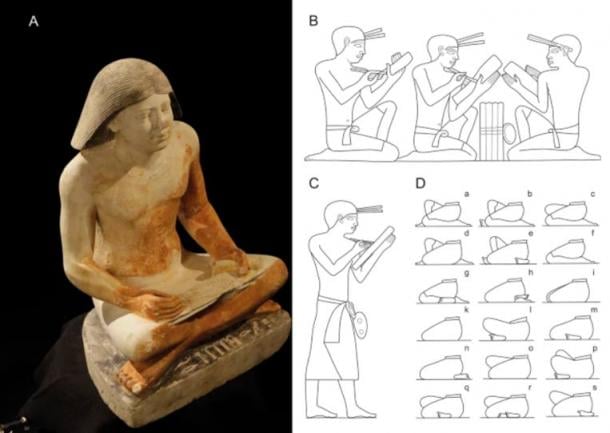

Working positions of scribes. ( A) cross-legged (sartorial) position (the scribal statue of the high-ranking dignitary Nefer, Abusir; photo Martin Frouz); ( B) kneeling-squatting position (wall decoration from the mastaba of the dwarf Seneb29); ( C) standing position (wall decoration from the mastaba of the dwarf Seneb29); ( D) based on tomb relief decoration, different position of the legs when sitting30. (Drawing Jolana Malátková/Nature)

Most ancient Egyptian scribes worked for royal courts or temples, or in various government offices. They functioned as the official record keepers of daily life in Egyptian society, and they were also historians and chroniclers whose duties required them to preserve the memory of the great accomplishments of the leaders of their day.

Ancient Egyptians believed that good fortune and the approval of the gods would be guaranteed as long as they continued to document their deeds for posterity, and scribes were rewarded handsomely for their literacy and for the writing skills they perfected to make this possible.

Much is known about the lives of Egyptian scribes, as their society’s obsession with record keeping ensured their activities and identities would be recorded and memorialized along with everything else. The Egyptians created statues and wall carvings that depicted scribes in action, revealing just how important their work was and what high status they enjoyed.

Statue of a scribe of the 5th dynasty, Museum at the necropolis of Saqqara; Catalogue Generale no. 63; statue belongs to a person called Ptahshepses and was found in Saqqara mastaba. (Harald Gaertner/CC BY-SA 3.0)

But the new study sponsored by the Czech Institute of Egyptology took historical research into the lives of ancient scribes in a whole new direction. This is the first analysis of their skeletal remains that has ever been undertaken, and it revealed that scribes experienced physical stress that had consequences similar to those caused by many types of manual labor.

In their examination of the remains of the scribes, the Czech researchers noticed clear signs of degenerative changes in their joints, consistent with the development of osteoarthritis. The areas most affected included the jawbone, the right thumb, the right collarbone, the right upper arm bone near the shoulder socket, the bottom of the right thigh bone where it connects with the knee, and the vertebrae located in the upper spine. The scribes also had indentations in their kneecaps and flattened surfaces on the lower parts of their right ankle bones.

Drawing indicating the most affected regions of the skeletons of scribes with higher prevalence of evaluated changes compared to reference group. (Drawing Jolana Malátková/Nature)

The type of damage discovered showed the scribes had spent long periods of time either sitting cross-legged or kneeling on their left legs with their right legs bent upwards to hold a papyrus on their laps. They would have also been hunched over while writing, assuming a position familiar to office workers today.

Thanks to the statues and wall reliefs that show scribes in action, researchers know all about how they sat, making it possible to correlate specific skeletal damage with these unfortunate postures.

“In a typical scribe’s working position, the head had to be bent forward and the spine flexed, which changed the center of gravity of the head and put stress on the spine,” anthropologist and study lead author Petra Brukner Havelková explained to Live Science. “And the correlation between [jaw disorders] and cervical spine dysfunction or neck/shoulder symptoms is well documented or supported by clinical studies.”

In addition to assuming unnatural postures, the scribes would have had to repeatedly chew on the ends of the rush stems they used to turn them into writing implements, and then pinch them tightly between their thumbs and forefingers while doing the actual writing. Even these activities were stressful and were likely responsible for much of the damage observed in the joints of the thumb and jaw.

Nice Work if You Can Get It

All in all, it seems that the life of a scribe in ancient Egypt was not as easy as might be supposed.

Its high status notwithstanding, the type of work scribes performed was repetitive and involved only a limited range of physical movements. Scribes sat in the same positions with the same postures for hours on end, concentrating on their writing and only rarely taking a break (they were under pressure to finish their assigned tasks as rapidly as possible).

“We may realize that although they were high-ranking dignitaries who belonged to the ancient Egyptian elite, they suffered the same worries as we do today and were exposed to similar occupational risk factors in their profession as most civil servants today,” Havelková noted.

But while they did pay a physical price for their privilege, scribes undoubtedly had access to the best healthcare services ancient Egyptian money could buy, and they certainly would have enjoyed lives of luxury once they decided to retire.

Top image: Statues depicting the high dignitary Nefer and his wife (Abusir, Egypt). Source: Martin Frouz and the Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University/Nature