🔴 Website 👉 https://u-s-news.com/

Telegram 👉 https://t.me/usnewscom_channel

You’ve made a huge political comeback. You’re deeply suspicious of the Washington bureaucracy. You’re contemptuous of liberal elites and the media they control, especially TV networks and The New York Times.

You’re trying to get America out of a war you didn’t start and which you regard as a drain on US resources. You’ve just delivered a massive shock to your allies. You really want them to rely less on the US for their security. You also want to counter their competition with US manufacturing. You’re aiming to achieve piece in the Middle East between Israel and everyone else. And you’re seeking to drive a wedge between Russia and China and exploit it to your advantage.

Congratulations, Donald Trump: You are officially Richard Nixon’s revenge. Not many presidents have sought to emulate Nixon since he was forced to resign in disgrace in August 1974. But you are going there. And in many ways you are right to do so. You just need to tread warily. There is a reason Richard is not fondly remembered today — except by you.

Many of my European friends are reeling from the events of the past two weeks. They feel the way many US allies felt on the night of Sunday, Aug. 15, 1971, after President Nixon had gone on TV to announce a 10% surcharge on all imports, a supposedly temporary suspension of the convertibility of the dollar into gold, and a 90-day wage and price freeze.

The “Nixon Shock” was in response to a run on gold by European holders of dollars, as well as a rise in US inflation. But it had a geopolitical counterpart. Nixon’s announcement a month earlier, on July 15, that he would be visiting Communist China the following year was as big a shock in Japan and Taiwan as the dollar devaluation a month later.

The Trump Shock

What we have seen since Feb. 18 has been the Trump Shock. It began with Trump blaming Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky for starting the war in Ukraine and being a dictator. Ten days later, in the Oval Office, Trump and Vice President J.D. Vance chewed Zelensky out for ingratitude and showed him the door. On March 4 Trump “paused” military aid to Ukraine. On the same day, he carried out his threat to impose 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico.

This has left American allies reeling, especially in Europe, where the incoming German chancellor, Friedrich Merz, has used remarkably strong language to condemn Trump, calling for “real independence from the USA.”

No one in Europe really understands the US-Ukraine minerals deal, nor why it didn’t get signed last week, nor why Trump is hanging Zelensky out to dry. But the Europeans finally get that European defense is on them. The years of riding on Uncle Sam’s nuclear coattails are over. In that sense, Trump’s shock tactics worked.

The reason the Europeans are baffled is that they think Trump wants to be emperor of the world — whereas the key to Trump’s Ukraine policy may not be hubris, but on the contrary a sense of weakness.

One possibility is that Trump and his closest advisers see clearly the weakness of the US position: the fiscal overstretch, now that we are spending more on interest on the debt than on defense, and the military understretch since we allowed our defense-industrial manufacturing base to shrivel.

Note the language Vance used when slamming me for criticizing the president’s Ukraine policy on X two weeks ago: “Is [Niall] aware of the reality on the ground, of the numerical advantage of the Russians, of the depleted stock of the Europeans or their even more depleted industrial base?” Note Elon Musk’s recent online debate with Ray Dalio on just how big Chinese manufacturing production is relative to the US and its allies.

Europeans obsess about Russia and Ukraine. But to my eyes, the Trump administration is more concerned about China. “I can tell you what,” President Trump said last week. “I have a great relationship with President Xi. I’ve had a great relationship with him. We want them to come in and invest. . . . The relationship we’ll have with China will be a very good one.” As Harvard’s Graham Allison has noted, Trump himself has been sweet-talking China, even as his administration has slapped on tariffs and tightened up tech restrictions.

Now what does Trump’s desire to go to Beijing remind you of? More and more commentators are spotting the Nixonian elements of Trump’s strategy. Nadia Schadlow, a key figure on the National Security Council in Trump’s first term, has noted how Nixon also believed in “more responsible participation by our foreign friends” in their own defense and based his foreign policy on the balance of power. Writing in The New York Times, Ross Douthat noted Trump’s debt to Nixon’s foreign policy realism. Former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis thinks we are heading for a new version of the Nixon Shock in the form of dollar devaluation.

The key idea doing the rounds in Washington is that Trump is attempting (in Edward Luttwak’s words) a “reverse-Nixon maneuver” to “prise Putin from Beijing.” Whereas Nixon went to China to exploit the Sino-Soviet split, “Trump has spotted [an] opportunity, realizing that in Putin’s pursuit of a favorable outcome in Ukraine there is an opportunity to detach him from Beijing.” Russell Berman and Kiron Skinner, who both served at the State Department in Trump’s first administration, make the same point in the American Spectator.

‘You are a great man’

There is a domestic dimension to the Trump-Nixon analogy, too. “He who saves his Country does not violate any Law,” Trump recently posted on Truth Social. It’s a phrase usually attributed to Napoleon. But Nixon famously told David Frost in a 1977 interview, “When the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.”

Trump and Nixon go way back. “I think that you are one of this country’s great men, and it was an honor to spend an evening with you,” Trump wrote to the former president in June 1982. They were regular correspondents in Nixon’s twilight years. In December 1987, Nixon told Trump that his wife Pat had seen Trump on Phil Donahue’s talk show. “As you can imagine,” he wrote, “she is an expert on politics and she predicts that whenever you decide to run for office you will be a winner!”

“You are a great man,” Trump told Nixon on the occasion of his 80th birthday in 1993, “and I have had and always will have the utmost respect and admiration for you. I am proud to know you.”

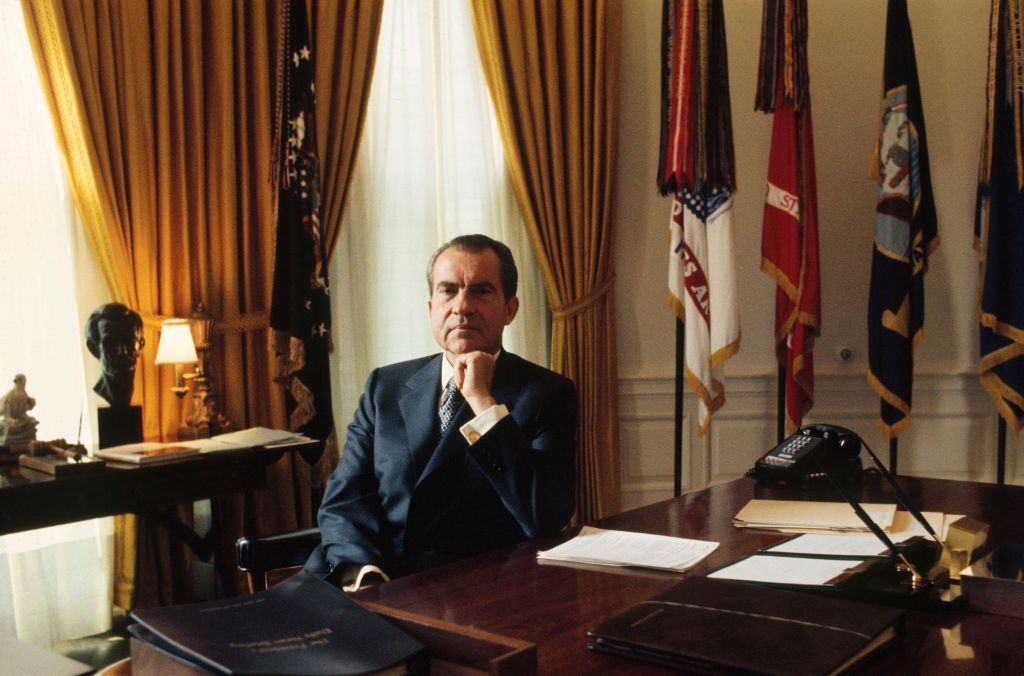

And Trump’s subsequent career has often echoed Nixon’s — not least his brushes with impeachment in his first term and his astonishing political comeback last year, which rivaled Nixon’s return from the political grave in 1968. As Harvard law professor Jack Goldsmith told The New Yorker recently, much of what the second Trump administration is doing can be seen as a sustained effort to restore the powers of the executive branch to where they were in 1972, when Nixon (pictured right) was at the height of his power. The question of “impoundment” — the president’s right not to spend funds Congress has appropriated — was one Nixon raised, only to have Congress slap it down in 1974.

The trouble with emulating Nixon is obvious. It didn’t end well. As the system of fixed exchange rates unraveled, the dollar slid. The outbreak of the Yom Kippur War in 1973 was followed by the Arab OPEC countries’ oil price hike — a shock administered to rather than by the US government. By the time Nixon was forced to resign over Watergate on Aug. 8, 1974, the US economy was in recession, with unemployment rising rapidly, and inflation at 11%. The S&P 500 declined 46% from its peak in the aftermath of Nixon’s landslide victory in November 1972 to its nadir in September 1974.

But the really big problem for President Trump is that Nixonian grand strategy is harder than it looks. To my mind, the probability of a Sino-Russian split must be very low as long as Xi and Putin are calling the shots in Beijing and Moscow. After all, it’s not as if Nixon brilliantly created the Sino-Soviet split. The USSR and the PRC were already close to border hostilities before he even entered the White House.

Pacific war games

As Sergey Radchenko shows in his brilliant book “To Run the World,” the two great communist regimes developed an obsessive antipathy toward one another during the 1960s, so that the Cold War in their minds became principally a competition between themselves, not against the US.

And it’s hardly an appealing analogy if Ukraine is going to end up being Trump’s (or maybe Vance’s) South Vietnam, as William McGurn has suggested.

Nixon had no illusions about the other members of the triangle. He knew the Soviets and the “Chicoms” for what they were. At times, by contrast, Trump seems too trusting of his Russian counterpart. And he may also underestimate Xi’s ability to resist his blandishments. If — as seems all too plausible — China makes a move against Taiwan on Trump’s watch, perhaps by simply “quarantining” the island, what exactly will Trump do?

The implications of a naval showdown over Taiwan are truly concerning. In most publicly known war games in recent years, the US struggles to prevail over China. In one game last year, organized by the Center for International and Strategic Studies, the US ran out of long-range anti-ship missiles “within the first week of the conflict.” That would not have been a conceivable scenario in any of the superpower showdowns in Nixon’s time.

I would have preferred more Reagan than Nixon in the foreign policy of Trump 2.0. But I take the president’s point that, as in the early 1970s, there are real limits to American power today. The challenge is to take a leaf out of Richard Nixon’s book — without in the end having the book thrown at you.