🔴 Website 👉 https://u-s-news.com/

Telegram 👉 https://t.me/usnewscom_channel

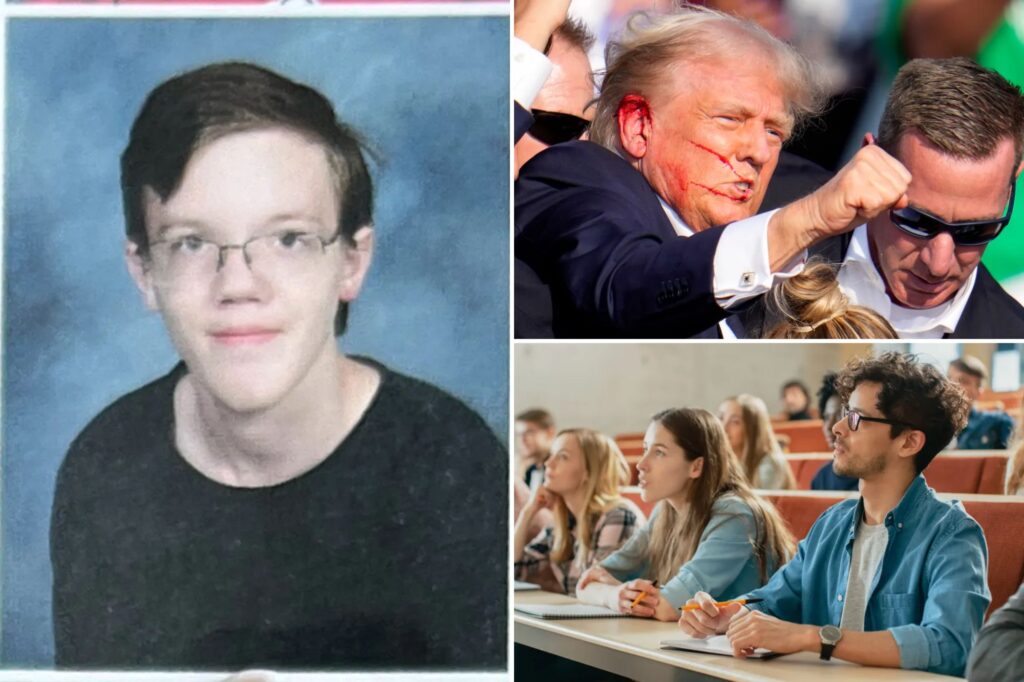

After more than six weeks of investigating Thomas Matthew Crooks’ life, the FBI remains stumped as to his motives for attempting to assassinate Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump in July.

The nation has moved on: President Biden dropped his re-election bid, Republicans and Democrats held their national conventions, and Kamala Harris turned around a presidential election cycle that Trump seemed almost fated to win.

Now students like me are heading back to colleges and universities, where the next round of campus protests are likely to be intensified by election fervor.

Little is known about why a 20-year-old kid like Crooks would try to assassinate the former president. But students my age don’t need to wonder.

Like many Americans, I was horrified by Crooks’ actions, but I wasn’t surprised.

Between emotional appeals from teachers and extremist messaging on social media, my generation has been inundated with dangerous political rhetoric for almost half our lives.

We don’t need FBI investigators to confirm what seems evident to us: Classroom echo chambers and social media are galvanizing disaffected young people toward extremist actions unimaginable a generation ago.

And more is almost certain to come.

I remember my first encounter with politics: I walked into an eerie classroom on November 9, 2016, just after Donald Trump became president-elect.

The teachers and principal hosted a “town hall” to give us — clueless Brooklynite 7th-graders — the microphone to voice our concerns.

The adults took turns bashing Trump before quietly sobbing into their tissues.

We didn’t compare candidates’ policy visions, or examine the electoral map.

We didn’t so much as watch an informational YouTube video to learn about the political system now being framed as “broken.”

It was an emotional dumpster fire.

I’m not alone. Jahmiel Jackson, a 22-year-old from Philadelphia who is now studying at the University of Chicago, had a nearly identical experience. And he’s a registered Democrat.

“I believe it happened in 10th grade,” Jackson said. “I remember my teachers coming in to cry. We didn’t have classes that day. I knew that something like a bomb had just dropped, but no one ever explained . . . why.”

For Jackson, the anti-Trump rhetoric would continue into college.

He recounted his first day taking a race and politics course: “We all had to go around and say, where were you the day Donald Trump was elected? As if this was 9/11 and we [were] saying, ‘Well, where were you when you saw the Twin Towers crash?’ ”

Kayla Hutt, 21, a student at New York University who considers herself a moderate, thinks professors have gone too far in promoting political awareness.

“We’ve passed the line where I’ve . . . heard of professors . . . offering extra credit to their students to go out and protest,” she said.

“I’ve seen two professors who have created groups outside of the class to have these discussions,” Hutt said. “That’s somewhat better because it’s outside the classroom, but at the same time, it’s an attempt to create an outside community of only like-minded people and trying to . . . push views on the students.”

Young people feel pressured to engage in this rhetoric both online and in casual conversations for fear of social consequences.

Jackson said at times he felt obligated or even bullied to appease his fellow classmates after he questioned their mostly progressive political narratives.

“A lot of the black students, especially the ones who were older than me said, ‘Well if you don’t stop talking about x problem, we’re gonna do this to you,’ ” said Jackson, who is African-American.

It’s not just Jackson.

Two in every three Americans under 30 have experienced online harassment.

Half of all US adults who have been harassed online say others have harassed them because of their political views.

Most of us use social media for mindless entertainment — we don’t care for colorful, virtue-signaling Instagram graphics.

But we also don’t want to be ostracized if our politics fail to skew with our cohort or crowds.

Yet even though few of the 33% of Americans our age who value social media as a venue to express their opinions castigate others online, it only takes one to ostracize us from our peers.

This is the world Crooks seems to have lived in, and it’s the one all of us Gen Zers are wading through right now as we head back to the classroom.

The grown-ups I speak to lament the polarized nation we live in today.

They recall an America without (or at least with far less) political animosity — where we can disagree and share a beer. That’s not the America my generation has known.

It’s true that the Secret Service failed on July 13, and the FBI isn’t informing Americans about the full extent of the Trump shooting.

But we’re ignoring the greatest truth of all: Our leaders failed to curb radical rhetoric in our schools, teach my generation that politics in conversation is impolite, and address my fellow Gen Zers cries for help as we battle a mental health crisis.

Thomas Matthew Crooks didn’t cause this generation’s crisis — but he may very well have been the product of it.

Daniel Idfresne is a junior at Syracuse University, a campus reform correspondent and a contributor at Young Voices.