🔴 Website 👉 https://u-s-news.com/

Telegram 👉 https://t.me/usnewscom_channel

Eight decades ago, the United States launched one of the most dramatic social changes in modern history: the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill.

Before that, mental health systems in New York and elsewhere consisted solely of state-run psychiatric institutions.

Regardless of your condition, all government had to offer you was confinement in an asylum.

Long story short, we decided not to do that anymore, and slashed over 90% of our public psych beds since the 1950s.

The result was twofold: Many people got more appropriate care and treatment through “community-based” outpatient programs.

Others wound up homeless, incarcerated and involved in violence.

But good news: deinstitutionalization in New York is finally over.

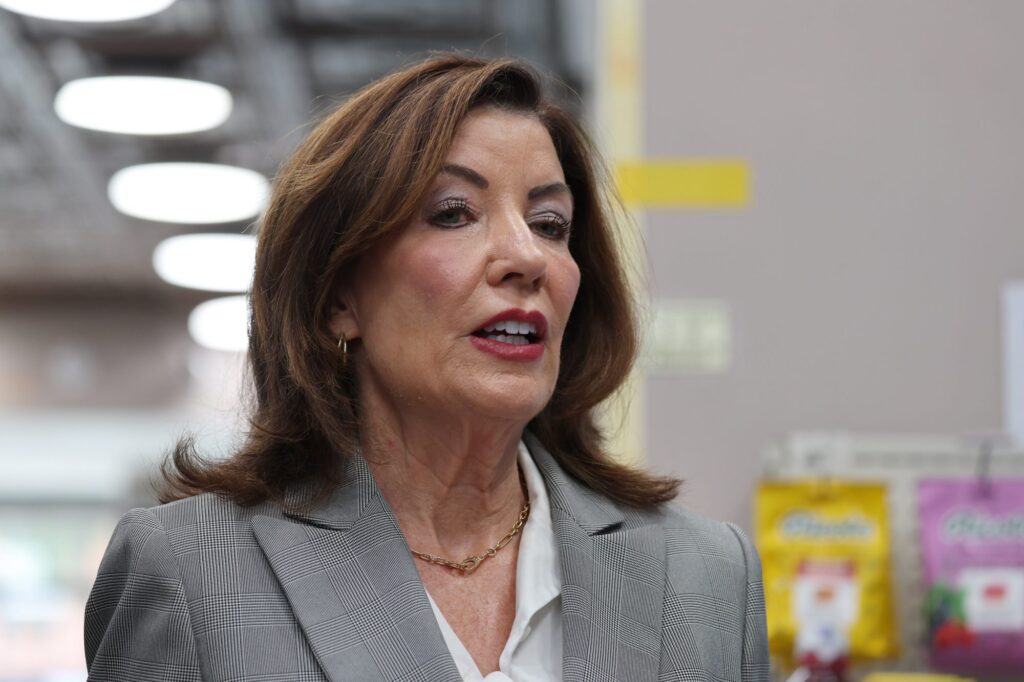

Since taking office in August 2021, Gov. Kathy Hochul has acted to stabilize New York’s psych bed supply, adding more than 300 beds to the total.

She has invested in state psychiatric institutions, boosted the Medicaid reimbursement for psych beds in general hospitals, pressured private health systems to replenish the beds they cut during COVID and loosened New York’s civil commitment standard.

These actions will benefit the seriously mentally ill, their families and the broader public — while benefiting the city budget.

Hochul’s predecessor Gov. Andrew Cuomo was a bed-slasher.

Cuomo shifted resources from psychiatric institutions to community programs, using the traditional argument that it would mean better care at a lower cost.

However, Cuomo’s bed reductions coincided with rising numbers of “emotionally disturbed person” calls fielded by the NYPD.

Spending on city mental-health shelters increased, and more seriously mentally ill individuals ended up locked in city jails.

In other words, what was sold as a cost shift from institutional to community-based programs turned out to be a cost shift from state to city taxpayers.

All this has improved under Hochul.

Mental health-related pressures on shelters, the police and other city systems remain acute, but they are no longer increasing at the rate they were under Cuomo’s deinstitutionalization regime.

New York still has far fewer public psychiatric hospital beds than many experts recommend — so while Hochul’s actions are a good start, more work remains.

Advocates of more state investment in inpatient psychiatric care face two main obstacles.

First, Hochul had to spend lavishly to get her bed additions through the state Legislature, throwing cash at community programs favored by critics of institutional care that weakened the opposition to expanding inpatient services.

In future budgets, though, state Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli and other fiscal watchdogs say state government won’t be able to spend that way.

A targeted state approach to mental health that focused more on untreated serious mental illness and far less on the “worried well” would be optimal — but politically is easier said than done.

Second, Mayor Eric Adams has been an indispensable advocate for saner mental health policies.

Should he lose his bid for reelection, New York will lose its greatest champion for reform through a focus on the hardest, most “service resistant” cases.

Adams and Hochul made a good team on mental health and other issues.

But this week she endorsed Zohran Mamdani, a critic of involuntary hospitalization, in the 2025 New York City race for mayor — no doubt hoping to maintain with Mamdani, the likely victor, the harmonious city-state relations she’s enjoyed with Adams.

However, harmony is not the historic norm for mayors and governors, and the mental-health crisis has often been a flashpoint between them.

And Albany unquestionably needs to lead: State government’s regulatory powers and oversight over Medicaid and the remaining institutional system make it best positioned to advance substantive mental health reform.

At the federal level, Congress must pass legislation to authorize more Medicaid funding for inpatient care in specialized psychiatric hospitals.

This week saw a positive development on that front when Brooklyn Democratic Rep. Dan Goldman filed legislation to do just that.

Goldman’s bill, the Michelle Alyssa Go Act, is named after the victim of a psychosis-driven subway pushing back in January 2022.

The mayor’s role is to play chief educator: State government may wield more authority, but the public will inevitably turn to the mayor for answers about pressing questions like the city’s mental-health crisis.

Adams made abandonment his theme — the idea that the status quo on mental health abandoned the seriously mentally ill at mass scale, putting both them and the general public at great risk.

It’s a valuable lesson that the average subway rider understands.

Whoever prevails on Nov. 4 would be wise to keep Adams’ and Hochul’s mental-health reforms on track.

Stephen Eide is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and author of the updated report “Systems Under Strain: Deinstitutionalization in New York State and City.”