🔴 Website 👉 https://u-s-news.com/

Telegram 👉 https://t.me/usnewscom_channel

The Los Angeles Unified School District is about to endure a probably ugly teachers strike.

But pouring more money into teacher salaries is not the answer.

Rather, only three reforms have any hope of improving performance in LA Unified: breaking up the district; parental choice; and Mississippi-style rigor.

Remember that this is the teachers union that delayed school reopenings after the Covid lockdown and attached extraneous political demands to the reopening process.

What the union is now demanding will leave the district unable to pay its bills within three years.

The union wants $1.3 billion more annual spending on its members — more than $4 billion over the next three years, as the district points out.

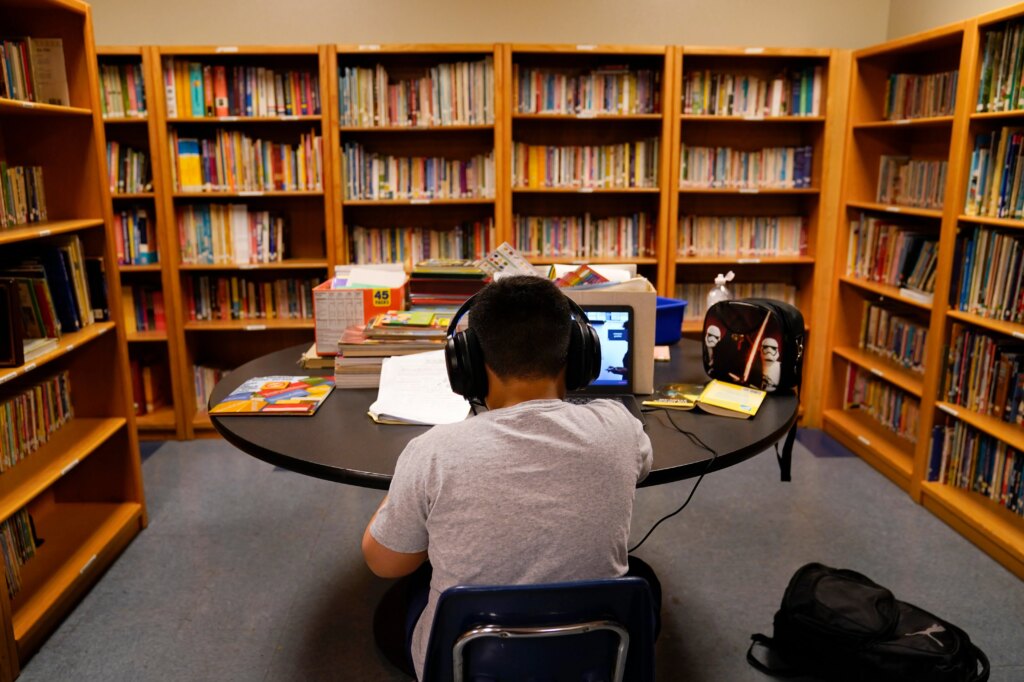

It is an appropriate occasion to review whether the teachers are successfully teaching their students.

They are not.

In LA Unified, student achievement scores on English and math are below the state average. Forty-six and a half percent of Los Angeles students are proficient or advanced in English Language Arts and 36.8% in math.

Three-quarters of black students are not performing at grade-level in math. Sixty-four percent of black students are not at grade level in reading.

Money for teacher salaries or other components of schooling is not what’s lacking.

Spending is high in Los Angeles and other California school districts.

But there are three reform strategies that might well boost student achievement.

The first option would be breaking up the district so that the new smaller, independent districts would compete against each other for parental favor.

Breaking up the currently gargantuan district would put activities at a more manageable, understandable level.

The new multiple districts would compete with each other, with parents seeking better schools by moving between districts at similar household-income levels.

Researchers such as Caroline M. Hoxby and Katie A. Sherron and Lawrence W. Kenny have shown that such interdistrict competition makes public schools more efficient.

The second option is parental choice. That means opportunity scholarships (vouchers), savings accounts, or charter schools.

Let’s just consider charter schools, which are public schools that aren’t managed by the district board and which are freed from almost all red tape.

Charter schools, as Thomas Sowell has pointed out, can and have closed the achievement gap between blacks and whites.

As of 2019, charter schools have done so as a whole in New York City.

Hoxby has shown that Harlem charters with the “poorest, mostly black” students closing the gap with students in “affluent” suburban Scarsdale public schools.

The National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST) studied Green Dot charter schools in Los Angeles.

The study found comparatively higher scores in Algebra I, Geometry, Algebra II, and Summative Math and in freshman high-school English.

But teachers unions hate charter schools, because they are almost entirely nonunion.

The last strategy could be called the Mississippi reform, which might happen anyway from the competitive pressure that would be exerted by either of the other two reforms.

Mississippi adopted an evidence-based systematic-phonics program for teaching reading. As a consequence, the state moved from 49th place in 2013 to 9th in 2024.

LA Unified adopted such a program beginning in the 2023-24 school year, and it is showing positive results.

Mississippi also put in place a strict policy that requires that third-graders be held back if they do not have a high enough score on the state’s reading test.

But in LA Unified, from 2017 to 2021, fewer than 1% of students were held back a grade. Students who don’t know how to read are just being promoted.

Breaking up the district, parental choice, and evidence-based teaching: These are the reforms that should be adopted.

Pouring in good money after bad — whether for teacher salaries or additional resources — will not do the trick.

Williamson M. Evers is a senior fellow at the Independent Institute and a former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Education for Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development.