🔴 Website 👉 https://u-s-news.com/

Telegram 👉 https://t.me/usnewscom_channel

The West’s fixation on therapy culture and ambiguous mental-health goals such as “wellness” often fails to address the needs of individuals with the most severe mental illnesses.

These conditions — which are associated with criminal behavior, chronic unemployment, and fractured relationships — demand urgent attention.

While reforms to expand residential treatment and comprehensive care are essential, what if a cost-effective solution could complement these interventions, stabilizing those at the highest risk of harming themselves or others?

Consider the story of Matt Baszucki.

In 2016, as a freshman at the University of California, Berkeley, he began displaying signs of psychosis.

By March, he’d spent two weeks in a psychiatric ward, diagnosed with bipolar disorder and prescribed medication.

Despite multiple treatments, his condition was deemed “treatment-resistant,” and no pharmaceutical combination could keep him stable or out of the hospital.

Desperate for answers, Matt’s parents — Roblox co-founder David Baszucki and novelist Jan Ellison — turned to Dr. Chris Palmer, a Harvard psychiatrist researching the link between metabolism and mental health.

Palmer, author of “Brain Energy” and director of the Metabolic and Mental Health Program at McLean Hospital, recommended the ketogenic diet, a low-carbohydrate, high-fat eating plan historically used to treat epilepsy.

Initially, Matt’s symptoms worsened on the diet, but under Palmer’s guidance, his condition gradually improved.

Eventually, his bipolar symptoms went into full remission. Today, nearly three years later, Matt remains symptom-free while requiring less and less medication.

“Matt’s story is not unusual,” Palmer explained to me via email. “Despite receiving the best care available, he continued to suffer. [But] metabolic treatments hold the potential to improve the lives of millions of people.”

NPR recently reported on the growing body of evidence linking the ketogenic diet to improved mental health. It highlighted stories like that of Iain Campbell, a researcher in Scotland who battled bipolar disorder until he tried the diet. Doctors like Dr. Georgia Ede, a Massachusetts psychiatrist and author of “Change Your Diet, Change Your Mind,” echo Palmer’s findings.

“The ketogenic diet is the most powerful therapeutic tool I have at my disposal,” Ede shared in an email. She noted that the diet improves the brain’s entire metabolic system, yielding transformative results in conditions ranging from ADHD and depression to psychosis and early Alzheimer’s.

Of course, despite its promise, the idea that dietary changes could meaningfully address mental illness faces skepticism.

The backlash journalist Gary Taubes endured two decades ago when he questioned the low-fat diet craze of the early 2000s and advocated for high-fat diets instead is illuminating.

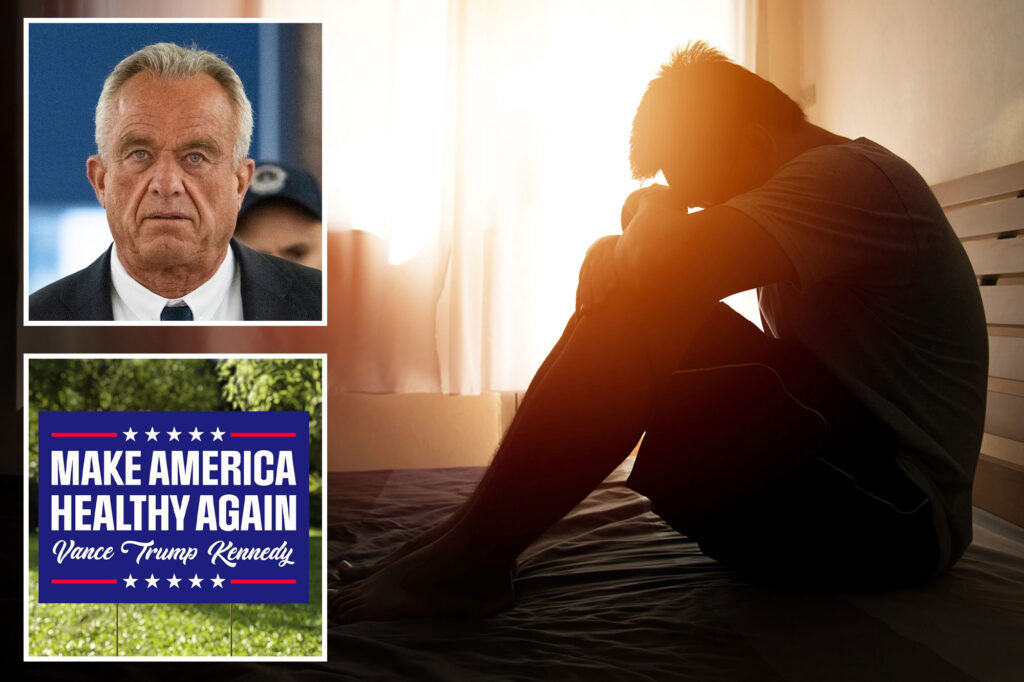

Yet, as public discourse evolves, the ketogenic diet may find greater acceptance — especially with figures like Robert F. Kennedy Jr. championing dietary reform as part of his “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) movement.

While Kennedy’s views on vaccines and autism are controversial, his MAHA initiative has sparked a national conversation about the link between diet and poor health.

In an August speech, Kennedy lamented the chronic disease epidemic fueled by poor nutrition.

Highlighting advocates like Dr. Casey Means and Calley Means, he criticized the US food system’s reliance on sugar and processed grains, which he linked to metabolic dysfunction and disease.

The Means siblings’ critique — articulated most prominently during an appearance on “The Tucker Carlson Show” that became the most shared episode of the year across the entire Apple Podcast platform — aligns with emerging research on how metabolic dysfunction contributes to mental illness.

Policymakers should seriously explore the ketogenic diet’s potential role in addressing these issues. While doctors like Ede emphasize that the keto diet — which some say could increase harmful cholesterol levels — isn’t a standalone solution, she sees it as a powerful complement to traditional treatments, if administered under medical supervision.

“Personalized treatment planning and professional support are necessary to ensure the transition to ketosis is safe and effective,” Ede explains. She suggests patients work with clinicians experienced in metabolic psychiatry and ketogenic therapies.

Beyond psychosis, the ketogenic diet shows promise in combating addictive behaviors that exacerbate societal issues. Ede notes improvements in patients struggling with gambling, binge eating, and alcohol use.

A recent study even found that patients undergoing alcohol withdrawal experienced fewer cravings and required less medication when following a ketogenic diet compared to the Standard American Diet (SAD).

Of course, the ketogenic diet isn’t a panacea for complex issues like psychosis or addiction. But backers say it can enhance the efficacy of costly treatments like pharmaceuticals and residential care. As Kennedy argued, addressing chronic disease isn’t just a moral imperative — it’s an economic one.

Chronic disease costs the US economy $4 trillion annually, “a 20% drag on everything we do,” he said. “We are poisoning the poor, we are systematically poisoning minorities across this country.”

The mental health and addiction crises underscore the need for innovative solutions. In cities like New York and Portland, tragic cases like Ramon Rivera — who, suffering from severe mental illness, killed three people in a recent NYC stabbing spree — illustrate the societal toll of untreated disorders.

If experts like Palmer and Ede are correct, ketogenic diets — despite their shortcomings — could play a key role in stabilizing individuals with mental illness or addiction.

As the MAHA movement gains traction, now is the time to consider the profound link between diet and mental health.