🔴 Website 👉 https://u-s-news.com/

Telegram 👉 https://t.me/usnewscom_channel

Is there generational tension in Hungary, and is a new political generation emerging? Can the 2026 parliamentary election be shaped— or even decided— by generational conflict?

Debates surrounding generational tensions and struggles have long been a recurring feature of social and political analysis. The fact that generations raised in different social environments see the world differently was highlighted in Mannheim’s seminal work.1 Discourse on perceived or actual conflicts between generations tends to intensify in the run-up to elections.

During the most recent parliamentary elections, considerable emphasis was placed on generational differences, accompanied by claims that the predominantly anti-government attitudes of young voters would exert a decisive influence on the electoral outcome and potentially bring about a change of government in Hungary. However, both the election results and subsequent analyses challenged this expectation, instead reinforcing interpretations that emphasized intergenerational cohesion rather than conflict.2

As the country approaches another parliamentary election in the spring of 2026, narratives of generational tension have once again gained prominence.3 Yet 2026 is evidently not 2022, which raises the question of whether contemporary discussions of intergenerational conflict rest on a solid empirical foundation. If such tensions do exist, it remains to be determined to what extent they can be characterized as political in nature.

‘As the country approaches another parliamentary election in the spring of 2026, narratives of generational tension have once again gained prominence’

The answer to the first question is definitely yes; the second, however, requires more detailed consideration. Research by the Youth Research Institute indicates that a substantial majority of individuals aged 15 to 39 (66 per cent) perceive a conflict between older and younger generations. By contrast, the proportion of respondents who report no such conflict is negligible (3 per cent). While respondents in the youngest cohort (15–17) also tend to perceive intergenerational conflict, they generally regard it as less pronounced. In contrast, most respondents under the age of 35 select the category ‘very significant conflict’. A similar pattern of more moderate assessments is observed among university graduates and individuals in favourable financial circumstances. No meaningful differences emerge between men and women, and perceptions are broadly comparable between urban and rural respondents.

Intergenerational conflict manifests across a range of contexts, and it is important to distinguish between direct experience within one’s own environment and indirect encounters. Accordingly, the Youth Research Institute survey also examined the domains in which such conflicts are most salient, as well as those characterized by greater intergenerational harmony.

The findings underscore the amplifying role of social media: nearly three-quarters (71 per cent) of respondents aged 15 to 39 report having encountered generational conflict on social media platforms. Public spaces, such as streets, represent the second most common setting, with 55 per cent reporting such experiences, reflecting the fact that these spaces are typically shared with strangers. Fewer than half of respondents report experiencing generational conflict in the workplace, approximately one-third within the family or in educational and institutional settings, and just over one-fifth within their neighborhoods.

When the sample is restricted to respondents who perceive either a conflict or a very significant conflict between younger and older generations, the frequency of reported conflict increases across all domains, although the relative ordering of settings remains largely unchanged. While sociodemographic differences in perceived generational conflict across specific contexts are generally limited, women consistently report experiencing conflict in a wider range of settings than men. Perceptions of conflict are also more pronounced among individuals aged 25 to 34 and increase in line with higher levels of educational attainment.

As elections draw nearer, it is pertinent to consider whether the perceived intergenerational conflict has a political dimension. An analysis of first-time voters following the 2022 elections concluded that an overwhelming majority voted in the same manner as their parents, suggesting an absence of pronounced generational tension within families.4 Findings from the Hungarian large-sample youth survey similarly indicate that young people aged 15–29 generally align with their parents’ views, both in terms of lifestyle and political orientations.5

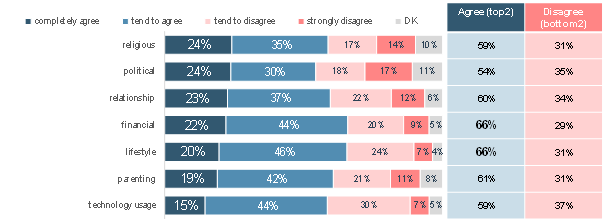

Recent research conducted by the Youth Research Institute further corroborates this pattern, demonstrating that agreement between young people and their parents is more prevalent than divergence. Approximately two out of three respondents tend to agree with their parents. The highest levels of agreement are observed in relation to financial matters and lifestyle choices. By contrast, the greatest degree of disagreement is found in the domains of technology use and politics; nevertheless, even in these areas, a majority of respondents report agreement with their parents (54 per cent and 59 per cent, respectively).

Notably, none of the sociodemographic background variables examinded, including gender, age group, or place of residence (capital city versus countryside), exhibit statistically significant explanatory power across the questions analysed. With regard to educational attainment, respondents with higher levels of education generally display greater alignment with their parents’ views. An exception is observed in the domain of technology use, where higher educational attainment is associated with a more critical stance towards parental attitudes.

The data provided by the Youth Research Institute yield several important insights. First, the existence of generational tension is clearly substantiated, at least from the perspective of young people. Second, the perceived intensity of intergenerational conflict varies markedly by context. It is generally more pronounced in impersonal settings, such as interactions with strangers, than within young people’s immediate social environments, most notably the family. Third, while tensions within the family may carry political implications, young people do not appear to perceive intergenerational political conflict as more salient than disagreements in other domains, such as the use of digital devices. Taken together, these findings indicate that although it would be inaccurate to deny the presence of generational conflict in Hungarian society with respect to political issues, the available evidence suggests that such conflicts are neither primarily political in character nor predominantly situated within the family.

What do these findings imply for the forthcoming elections, and to what extent can young voters influence the outcome? In Hungary, there are approximately 2.5 million adults under the age of 40. If this cohort were to participate at the same rate as in the 2022 parliamentary elections, their turnout would amount to an estimated 1.7 million votes. More realistically, however, given the persistently lower electoral participation among younger voters, turnout is likely to be closer to 1.5 million votes, which is still a politically significant figure.

‘Generational divisions are unlikely to serve as the decisive factor determining the outcome of the 2026 parliamentary election’

Although political interest among young people has increased in recent years,6 generational political movements that emerged after the turn of the millennium have achieved only limited and temporary success. Parties and initiatives once associated with youth mobilization, such as Jobbik and Momentum, or movements including Critical Mass, the Student Network, and FreeSZFE, have either lost political relevance or largely ceased to operate. At present, there are no influential political organizations composed predominantly of individuals under the age of 40.

Nevertheless, both the governing parties and the opposition continue to direct targeted appeals towards young voters. Opinion polls conducted last year, despite their otherwise inconsistent results, consistently indicated higher levels of support for the opposition among young people than for the governing parties.7 However, the experience of the 2022 elections, together with the findings of the present study, suggest a more nuanced interpretation. Taken together, the evidence indicates that while young voters constitute an important electoral group, generational divisions are unlikely to serve as the decisive factor determining the outcome of the 2026 parliamentary election.

Related articles:

The post Generation Gap or Reality Gap? — The Nature of Mediatized Perceptions and Social Reality appeared first on Hungarian Conservative.

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://www.hungarianconservative.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.