🔴 Website 👉 https://u-s-news.com/

Telegram 👉 https://t.me/usnewscom_channel

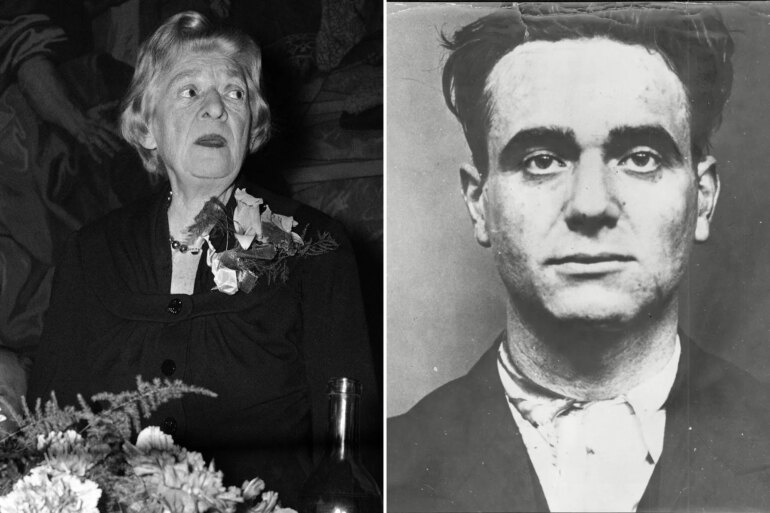

Janet Flanner, a struggling novelist with an unconventional lifestyle, was one of countless Americans living in 1920s Paris, now known as “The Lost Generation.”

Her friend Jane Grant, a New York Times reporter, was starting an ambitious magazine with her husband called The New Yorker.

Grant loved Flanner’s letters about life in Paris so much, she hired her to write them as a magazine column.

Soon, Flanner was no longer “lost” but had found her life’s calling. Her groundbreaking “Letter from Paris” society column, under the nom de plume Genêt, would run for decades.

One French story came to symbolize the danger to Western Europe in the late 1930s: that of German serial killer Eugen Weidmann, who would become the last man publicly guillotined in France.

In the new book “The Typewriter and the Guillotine: An American Journalist, a German Serial Killer, and Paris on the Eve of WWII,” Mark Braude weaves together the tales of these two foreigners living in France and gives readers a remarkable look at the City of Light in the growing shadow of Nazi Germany.

The widespread view in America following the First World War was that the British had lied us into the conflict. Hoping to stay out of the next war, the public became insatiable for foreign news, and papers started large international divisions.

The top foreign correspondents became some of the biggest celebrities of their era, though as writers on current events, few remain well known.

Ironically, it was these same foreign correspondents who did the most to warn Americans of the threats of Hitler’s rise and advocate for American involvement in Europe.

Most were conventional journalists with strong political views, while others were idealistic adventurers like Flanner’s friend Ernest Hemingway, the one who remains the most famous.

Flanner was something of the odd woman out, an assiduously apolitical former minor film critic writing about French culture and society.

But as the 1930s wore on and the political consumed the personal, she increasingly felt it necessary to use culture to inform the public about the continent’s tensions.

I happen to have read Flanner’s main collection of prewar writings, “Paris Was Yesterday,” last year for no reason besides that I saw it at a thrift shop and like France and the 1930s. Much of the book is miscellanea only of interest to scholars of the era, but there are also timeless true-crime stories and dispatches from key moments in the lead-up to the Second World War.

She was a talented prose stylist who turns a clever phrase, but what strikes the modern reader is this was innovative at the time: Her style was so influential that without knowing it many now write like her or at least try to.

In 1925, while still finding her voice, she said of Dada movement founder Tristan Tzara, “No one has written more foolishly at times, but many have written almost as foolishly and never once so well.”

It was this sort of understated but incisive irony with which she’d later write one of the first major profiles of Adolf Hitler for the American press.

Braude describes her “new kind of journalism” as “the classicNew Yorker tone of its founding era: wry and irreverent, immune to hypocrisy and attuned to absurdity.”

The book’s other subject, Eugen Weidmann, was also, unfortunately, something society has grown used to: a violent man who believes he’s a genius and feels mistreated by the world.

His crimes were not compulsive but for profit. The ex-con escaped Germany for France, hoping to start a notorious career as a Chicago-style gangster.

He usually killed with a single gunshot to the back of the neck, which, as widely noted at the time, was the Gestapo’s preferred method of execution.

He could kill the defenseless but was no genius at making money off it. The crimes that would cost him his head barely covered the rent on a small home he shared with his co-conspirators.

In the time before Weidmann’s crime spree, Flanner gained experience writing about evil.

Her profile of Hitler, researched through surreptitious observation with no request for interviews, began running on leap day 1936. It was controversial because she wanted to be neutral and because she wrote it like a celebrity profile.

She opened by saying it was odd that a celibate, nonsmoking, teetotaling, vegetarian should be “dictator of a nation devoted to splendid sausages, cigars, beer, and babies.”

She speculated he avoided alcohol and nicotine because he was a malformed eccentric and didn’t want to make it worse.

Hitler already had the reputation, as he does now, as a one-dimensional evil clown. Flanner wanted to make it clear he was both unique and uniquely dangerous.

Even so, some saw it as too sympathetic due to her detached tone and determination to do more than just denounce fascism.

Further, when she covered the Berlin Olympics, she was impressed by the show Germany put on and noticed that, strangely, in Nazism’ early years the recently distressed Germans had a new optimism and kindness, while the alarmed French were becoming xenophobic and dysfunctional.

Later, though Flanner loathed war and once wrote, “I am like many women I think, a uterine pacifist,” she increasingly felt called to tell the American public about the danger to Europe.

She had avoided mentioning the Spanish Civil War, for example, but later used a bullfight in southern France to talk about the conflict, explaining to readers that because fighting bulls come from Fascist Spain and great matadors come from Loyalist Spain, the good bullfights were now all in France.

Being a society columnist, she spent much of the rest of her article on matador outfits. “If a journalistic prize is ever given for the worst sports writer,” her friend Hemingway told her, “I’m going to see you get it, pal, for you deserve it. You’re perfectly terrible.”

Flanner described Weidmann’s first victim, Jean de Koven, a young Jewish dancer from Brooklyn, thus: “An average American tourist in Paris but for two exceptions. She never set foot in the Opera, and she was murdered.”

The police initially wouldn’t look for her, on the grounds that American girls arriving in Paris were always going missing on a fling and showing up a few days later embarrassed but unharmed, which sounds extremely sexist but was also surely true.

Police even assumed the ransom note was a publicity scheme.

When her American Express traveler’s checks started showing up with forged signatures, they did take it seriously, but de Koven was not found until Weidmann had committed five more homicides.

He confessed to burying her under his porch. The police never considered the case might be connected to the murderer they were hunting.

The Weidmann trial was a sensation thanks to the international aspect but also because ladies found him handsome and sent him letters in jail.

Flanner calls it testament to the rationality of the French that his race was not held against him, though his own lawyer argued Germans are naturally prone to such violence and he should be spared the blade.

Weidmann was executed by guillotine in public in June 1939.

He met his death calmly, but the crowd was large and rowdy. The scene was described as like a medieval festival.

This was all caught on film and is available on the internet. The actor Christopher Lee is visible in the crowd as a young man.

The French government realized that if it were to be the civilized alternative to Nazism, this practice had to be ended immediately, and it was.

As for Flanner, she left France in fall 1939, spending the war in New York. She wrote profiles of de Gaulle and Pétain and ultimately joined the Women’s Army Corps as a journalist.

After its liberation, she returned to her beloved Paris to write about food rationing and stolen artwork.

She visited the Buchenwald concentration camp with the army and was left deeply shaken. She also covered the Nuremberg trials.

After the war, she continued to write her New Yorker “Letter from Paris” until 1975 — 50 years at the same column, minus five lost to the Nazi occupation.

Now, a century after Flanner’s first columns, many like to compare our society to 1930s Europe without knowing anything about 1930s Europe.

While one can find parallels in any time, the decade was much more than just the rise of Hitler and Munich. Europe had been destroyed at its zenith in WWI, and much of the generation who should have been taking over was dead.

When it began to recover, the global depression hit, harming free-market democracies much more than fascist states.

Flanner witnessed a professor in Germany wiping up crumbs after a modest faculty meal to bring home to his family, but when Weidmann got out of prison after four years he saw clean streets and new construction.

France’s Third Republic was itself failing but had guaranteed the security of several new states. The continent was awash with paramilitaries, and almost all but the northwest was ruled by dictators.

Liberal democracy wasn’t just challenged — in most of Europe it had already failed.

The 1930s were a fascinating decade, but the conclusion one would come to by studying them is they have almost nothing in common with America today.

Challenges a free government always faces are not like Hitler overthrowing the republic, enforcing the law is not “Gestapo tactics” of summary execution by a single gunshot to the neck, and every compromise is not betraying Czechoslovakia.

America is a prosperous country with strong institutions, and while some of them may not be working well, the overwhelming desire is to make them work better for the public, not to do away with them entirely.

While Flanner’s and Weidmann’s lives were not intertwined beyond her covering his story, by using the killer’s sordid tale as a hook, “The Typewriter and the Guillotine” brings 1930s Paris to life for modern readers.

Perhaps more important, while Weidmann will always have his place as a grim “last” in French history, Flanner, a now-forgotten legend of New York media, deserves to be remembered and celebrated.

Brad Pearce writes The Wayward Rabbler on Substack.