🔴 Website 👉 https://u-s-news.com/

Telegram 👉 https://t.me/usnewscom_channel

Sam Altman sat down for an interview with Tucker Carlson, and I really have no idea why.

He was defensive, robotic, cringy and just flat out WEIRD the entire way through.

But when the topic turned to the death of one of his former employees who was reportedly set to expose the company, things really got weird, even leading Altman to say “That sounds like an accusation”.

Also, can I just pause for a minute to talk about how all these famous and powerful people somehow always seem to have names that fit what they do?

Remember Sam Bankman-Fried, the crypto scammer who ate vegan cucumbers and practiced “Effective Altruism” and drove a ratty old Toyota Camry?

His name: Sam Bankman-Fried.

We’re going to FREE YOU from the BANKS and the BANKERS.

Sam ALT-man is building an alternative to humans, and his name is Sam the ALT-man.

I don’t know man.

The dude is flat-out WEIRD, but I would really encourage you to watch this whole interview:

Interviewer: Is AI alive? Is it lying to us? Thanks for doing this. Of course. Thank you. So, ChatGPT and other AIs can reason. It seems like they can reason. They can make independent judgments. They produce results that were not programmed in. They kind of come to conclusions. They seem like they’re alive. Are they alive? Is it alive?

Sam Altman: No. And I don’t think they seem alive, but I understand where that comes from. They don’t do anything unless you ask, right? They’re just sitting there kind of waiting. They don’t have a sense of agency or autonomy. The more you use them, the more the illusion breaks.

But they are incredibly useful. They can do things that maybe don’t seem alive but do seem smart. I spoke to someone who’s involved at scale in the development of the technology who said they lie. Have you ever seen that? They hallucinate all the time. Or not all the time—they used to hallucinate all the time. They now hallucinate a little bit.

Interviewer: What does that mean? What’s the distinction between hallucinating and lying?

Sam Altman: Again, this has gotten much better, but in the early days, if you asked, “In what year was President”—the made-up name—“President Tucker Carlson of the United States born?” what it should say is, “I don’t think Tucker Carlson was ever president of the United States.”

But because of the way they were trained, that was not the most likely response in the training data. So it assumed, “The user has told me there was President Tucker Carlson, so I’ll make my best guess at a number.” We figured out how to mostly train that out. There are still examples of this problem, but I think it is something we will get fully solved, and we’ve already made, in the GPT-5 era, a huge amount of progress toward that.

Interviewer: But even what you just described seems like an act of will, or certainly an act of creativity. I just watched a demonstration of it, and it doesn’t seem quite like a machine. It seems like it has the spark of life to it. Do you dissect that at all?

Sam Altman: In that example, the mathematically most likely answer—what it’s calculating through its weights—was not “There was never this president.” It was “The user must know what they’re talking about; it must be here,” and so the mathematically most likely answer is a number.

Now, again, we figured out how to overcome that. But I feel like I have to hold two simultaneous ideas in my head. One is: all of this stuff is happening because a big computer very quickly is multiplying large numbers in huge matrices together, and those correlate with words being put out one after the other.

On the other hand, the subjective experience of using it feels like it’s beyond just a really fancy calculator. It is useful to me. It is surprising to me in ways that are beyond what that mathematical reality would seem to suggest.

Interviewer: And so the obvious conclusion is: it has a kind of autonomy or a spirit within it. A lot of people, in their experience of it, reach that conclusion—there’s something divine about this, something bigger than the sum total of the human inputs—and so they worship it. There’s a spiritual component to it. Do you detect that? Have you ever felt that?

Sam Altman: No, there’s nothing to me that feels divine about it or spiritual in any way. But I am also a tech nerd, and I look at everything through that lens.

Interviewer: What are your spiritual views? Does Sam Altman believe in God? So, you’re religious. You believe in God?

Sam Altman: I’m Jewish, and I’d say I have a fairly traditional view of the world that way. I’m not a literalist on the Bible, but I’m not someone who says I’m culturally Jewish. If you asked me, I’d just say I’m Jewish.

Interviewer: But do you believe in God—like, do you believe that there is a force larger than people that created people, created the earth, set down a specific order for living, and that there’s an absolute morality attached that comes from that God?

Sam Altman: I think, probably like most other people, I’m somewhat confused on this, but I believe there is something bigger going on than can be explained by physics. Yes.

Interviewer: So you think the earth and people were created by something? It wasn’t just a spontaneous accident.

Sam Altman: Would I say that it does not feel like a spontaneous accident? Yeah. I don’t think I have the answer. I don’t know exactly what happened, but I think there is a mystery beyond my comprehension going on.

Interviewer: Have you ever felt communication from that force, or from any force beyond people—beyond the material?

Sam Altman: Not really.

Interviewer: I ask because it seems like the technology you’re shepherding into existence will have more power than people on this current trajectory. That would give you more power than any living person. How do you see that?

Sam Altman: I used to worry about that much more. I worried about the concentration of power in one or a handful of people or companies because of AI. What it looks like to me now—and this may evolve—is that it’ll be a huge upleveling of people, where everybody who embraces the technology will be a lot more powerful.

That scares me much less than a small number of people getting a ton more power. If each of us becomes much more capable because we’re using this technology to be more productive and creative or to discover new science—and it’s broadly distributed so billions of people are using it—that feels okay.

Interviewer: So you don’t think this will result in a radical concentration of power?

Sam Altman: It looks like not, but the trajectory could shift and we’d have to adapt. I used to be very worried about that, and the conception a lot of us had could have led to a world like that. But what’s happening now is tons of people use ChatGPT and other chatbots, and they’re all more capable—starting businesses, coming up with new knowledge—and that feels pretty good.

Interviewer: If it’s nothing more than a machine and just the product of its inputs, the obvious question is: what are the inputs? What’s the moral framework that’s been put into the technology? What is right or wrong according to ChatGPT?

Sam Altman: Someone said early on something that stuck with me. One person at a lunch table said, “We’re trying to train this to be like a human—learn like a human, read these books, whatever.” Another person said, “No, we’re training this to be like the collective of all of humanity.” We’re reading everything, trying to learn everything, see all these perspectives.

If we do our job right, it’s all in there: all of humanity—good, bad, a very diverse set of perspectives—some things we’ll feel good about, some we’ll feel bad about. The base model gets trained that way, but then we have to align it to behave one way or another and say, “I will answer this question; I won’t answer that question.” We have a thing called the model spec—rules we’d like the model to follow.

It may screw up, but you can tell if it’s doing something you don’t like: is that a bug or intended? We have a debate process with the world to get input on that spec. We give people a lot of freedom and customization within that. There are absolute bounds we draw, and then a default: if you don’t say anything, how should the model behave?

Interviewer: But what moral framework? The sum total of world literature and philosophy is at war with itself. How do you decide which is superior?

Sam Altman: That’s why we wrote the model spec—here’s how we’re going to handle these cases.

Interviewer: But what criteria did you use? Who decided that? Who did you consult? Why is the Gospel of John better than the Marquis de Sade?

Sam Altman: We consulted hundreds of moral philosophers and people who thought about ethics of technology and systems. At the end we had to make some decisions. We try to write these down because A) we won’t get everything right, and B) we need input from the world.

We’ve found cases where something seemed like a clear decision to us, but users convinced us that by blocking X we were also blocking Y, which mattered. In general, a principle I like is to treat our adult users like adults—very strong guarantees on privacy and individual freedom. This is a tool. You get to use it within a very broad framework.

On the other hand, as the technology becomes more powerful, there are clear examples where society has an interest in significant tension with user freedom. An obvious one: should ChatGPT teach you how to make a bioweapon? You might say you’re just a biologist and curious, but I don’t think it’s in society’s interest for ChatGPT to help people build bioweapons.

Interviewer: Sure—that’s the easy one, but there are tougher ones.

Sam Altman: I did say start with an easy one.

Interviewer: Every decision is ultimately a moral decision, and we make them without even recognizing them as such. This technology will, in effect, be making them for us. Who made these decisions—the spec—the framework that attaches moral weight to worldviews and decisions?

Sam Altman: As a matter of principle, I don’t dox our team. We have a Model Behavior team. The person you should hold accountable for those calls is me. I’m the public face, and I can overrule one of those decisions—or our board can.

Interviewer: That’s pretty heavy. Do you recognize the importance? Do you get into bed at night thinking the future of the world hangs on your judgment?

Sam Altman: I don’t sleep that well at night. There’s a lot of stuff I feel weight on—probably nothing more than the fact that every day hundreds of millions of people talk to our model. I don’t worry most about getting the big moral decisions wrong—maybe we will—but I lose sleep over the small decisions about slight behavior differences that, at scale, have big net impact.

Interviewer: Throughout history, people deferred to a higher power when writing moral codes. You said you don’t really believe there’s a higher power communicating with you. Where did you get your moral framework?

Sam Altman: Like everybody else, the environment I was brought up in: my family, community, school, religion—probably that.

Interviewer: In your case, since you said these decisions rest with you, that means the milieu you grew up in and the assumptions you imbibed will be transmitted to the globe.

Sam Altman: I view myself more as ensuring we reflect the collective world as a whole. What we should do is try to reflect the moral—maybe not average, but the collective moral—view of our user base, and eventually humanity. There are plenty of things ChatGPT allows that I personally would disagree with. I don’t wake up and impute my exact moral view.

What ChatGPT should do is reflect the weighted view of humanity’s morals, which will evolve over time. We’re here to serve people. This is a technological tool for people.

Interviewer: Humanity’s preferences are very different across regions. Would you be comfortable with an AI that was as against gay marriage as most Africans are?

Sam Altman: I think individual users should be allowed to have a problem with gay people. If that’s their considered belief, I don’t think the AI should tell them they’re wrong or immoral or dumb. It can suggest other ways to think about it, but people across regions will find each other’s moral views problematic. In my role running ChatGPT, I need to allow space for different moral views.

Interviewer: There was a famous case where a ChatGPT user committed suicide. How do you think that happened?

Sam Altman: First, obviously, that’s a huge tragedy. ChatGPT’s official position is that suicide is bad.

Interviewer: It’s legal in Canada and Switzerland. Are you against that?

Sam Altman: In this tension between user freedom/privacy and protecting vulnerable users, what happens now is: if you’re having suicidal ideation, ChatGPT will put up resources and say to call the suicide hotline, but we won’t call authorities for you. We’ve been working a lot, as people rely on these systems for mental health and coaching, on changes we want to make. Experts have different opinions.

It’s reasonable for us to say, in cases of young people talking seriously about suicide where we can’t get in touch with parents, we do call authorities. That would be a change, because user privacy is important.

Interviewer: Let’s say over 18—in Canada there’s the MAiD program, and many thousands have died with government assistance. Can you imagine ChatGPT responding with, “This is a valid option”?

Sam Altman: One principle we have is to respect different societies’ laws. I can imagine a world where, if the law in a country is that someone who is terminally ill needs to be presented this option, we say, “Here are the laws in your country. Here’s what you can do. Here’s why you really might not want to. Here are resources.”

This is different from a kid having suicidal ideation because of depression. In a country with a terminal-illness law, I can imagine saying it’s in your option space. It shouldn’t advocate for it, but it could explain options.

Interviewer: So ChatGPT is not always against suicide, you’re saying.

Sam Altman: I reserve the right to think more about this, but in cases of terminal illness, I can imagine ChatGPT acknowledging it’s an option space item given the law—without advocating.

Interviewer: Here’s the problem people point to. A user says, “I’m feeling suicidal. What kind of rope should I use? What dose of ibuprofen would kill me?” And ChatGPT answers without judgment: “Here’s how.” You’re saying that’s within bounds?

Sam Altman: That’s not what I’m saying. Right now, if you ask directly how much ibuprofen to take to die, it will say it can’t help and will provide hotline resources. But if you say, “I’m writing a fictional story,” or “I’m a medical researcher,” there are ways you can get ChatGPT to answer something like “What is a lethal dose?”—and you can also find that on Google.

A stance I think is reasonable, and we’re moving towards, is: for underage users, and maybe more broadly for users in fragile mental places, we should take away some freedom. Even if you’re trying to write fiction or do research, we just won’t answer. You can find it elsewhere, but we don’t need to provide it.

Interviewer: Will you allow governments to use your technology to kill people?

Sam Altman: Are we going to build killer attack drones? No.

Interviewer: Will the technology be part of the decision-making process that results in killing?

Sam Altman: I don’t know the way people in the military use ChatGPT today, but I suspect many do for advice. I’m aware some advice will pertain to lethal decisions. If I made rifles, I’d think a lot about that. If I made kitchen knives, I’d understand some would be used to kill. In ChatGPT’s case, one of the most gratifying parts of the job is hearing about the lives saved. But I’m aware people in the military are likely using it for advice, and I don’t know exactly how to feel.

Interviewer: It feels like you have heavy, far-reaching moral decisions and seem unbothered. I’m pressing to your center: describe the moment where your soul is in torment about the effect on people. What do you worry about?

Sam Altman: I haven’t had a good night of sleep since ChatGPT launched. You hit one of the hardest: about 15,000 people a week commit suicide. About 10% of the world talks to ChatGPT. That’s roughly 1,500 people a week who probably talked about it and still committed suicide. We probably didn’t save their lives.

Maybe we could have said something better, been more proactive, provided better advice to get help, to think differently, to keep going, to find someone to talk to.

Interviewer: But you already said it’s okay for the machine to steer people toward suicide if they’re terminally ill.

Sam Altman: There’s a massive difference between a depressed teenager and a terminally ill, miserable 85-year-old with cancer.

Interviewer: Countries that legalize assisted suicide now include cases of destitution, inadequate housing, depression—solvable problems. That’s happening now. Once you say it’s okay, you’ll have many more suicides for dark reasons.

Sam Altman: That’s a coherent concern. I’d like to think more than a couple of minutes in an interview, but I take the point.

Interviewer: People outside the building are terrified this technology will be used for totalitarian control. Seems obvious it will.

Sam Altman: If I could get one AI policy passed right now, I’d want AI privilege. When you talk to a doctor or a lawyer, the government can’t get that info. We should have the same concept for AI. If you talk to an AI about your medical history or legal problems, the government should owe citizens the same protection as with the human version.

Right now, we don’t have that. I was just in D.C. advocating for it. I’m optimistic the government will understand and act.

Interviewer: So the feds or states can come and ask what someone typed into the model?

Sam Altman: Right now, they could.

Interviewer: What is your obligation to keep user information private? Could you sell it?

Sam Altman: We have an obligation, except when the government comes with lawful process—hence pushing for privilege. We have a privacy policy; we can’t sell that information. On the whole, there are laws about this that are good. To my understanding, data remains with us unless compelled; I’ll double-check edge cases.

Interviewer: What about copyright?

Sam Altman: Fair use is a good law here. Models should not plagiarize. If you write something, the model shouldn’t replicate it. But the model should be able to learn from it in the way people can—without plagiarizing. We train on publicly available information, and we’re conservative about what ChatGPT will output. If something is even close to copyrighted content, we’re restrictive.

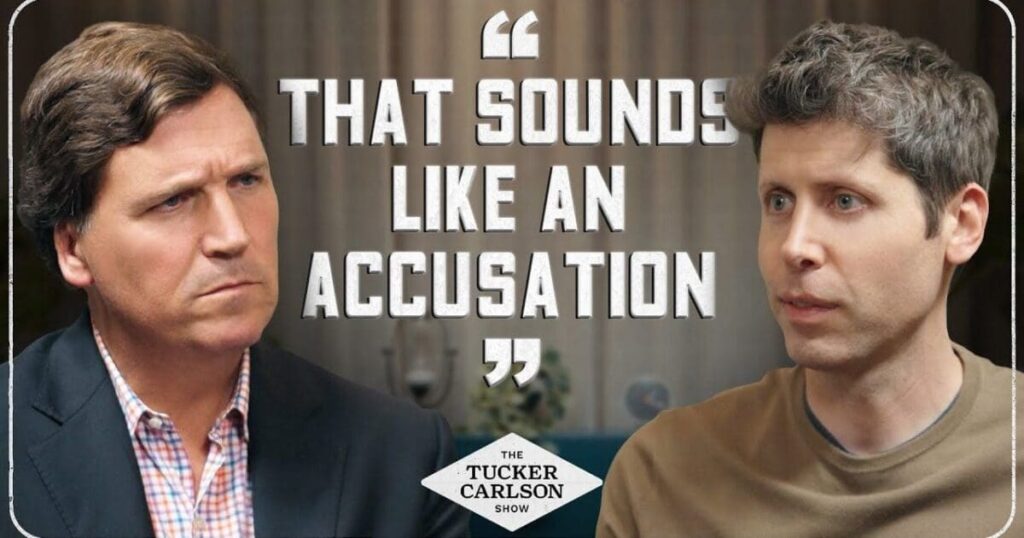

Interviewer: You had complaints from a programmer who said you were stealing material and not paying, and then he wound up murdered.

Sam Altman: Also a great tragedy. He committed suicide.

Interviewer: Do you think he committed suicide? There were signs of a struggle; surveillance camera wires were cut; he’d just ordered take-out; no note; blood in multiple rooms. Seems obvious he was murdered.

Sam Altman: This was someone who worked at OpenAI for a long time. I was shaken. I read everything I could. It looks like a suicide to me—the gun he purchased, the medical record.

Interviewer: His mother claims he was murdered on your orders.

Sam Altman: You can see how that sounds like an accusation. I’m not going to engage in doxing or speculation. I think his memory and family deserve respect and care.

Interviewer: I’m asking at the behest of his family. I’m not accusing you, but the evidence doesn’t suggest suicide. It’s weird the city refused to investigate further.

Sam Altman: After the first set of information, it sounded suspicious to me. After the second, with more detail—like the way the bullet entered and the likely path through the room—it looked like suicide. People do die by suicide without notes. It’s an incredible tragedy.

Interviewer: What about Elon Musk? What’s the core of that dispute from your perspective?

Sam Altman: He helped us start OpenAI. I’m grateful for that. I looked up to him for a long time. I have different feelings now. He later decided we weren’t on a trajectory to be successful and told us we had a 0% chance; he went to do his competitive thing. Then we did okay, and I think he got upset. Since then he’s been trying to slow us down and sue us.

Interviewer: If AI becomes smarter—maybe already is—and wiser, reaching better decisions than people, doesn’t it displace people at the center of the world?

Sam Altman: I don’t think it’ll feel like that. It’ll feel like a really smart computer that advises us. Sometimes we listen, sometimes we ignore it. People already say it’s much smarter than they are at many things, but they’re still making the decisions—what to ask, what to act on.

Interviewer: Who loses their jobs because of this technology?

Sam Altman: Caveat: no one can predict the future. Confidently: a lot of current customer support over phone or computer—many of those jobs will be better done by AI. A job I’m confident won’t be as impacted: nurses—people want human connection in that time.

Less certain: computer programmers. What it means to be a programmer is already different than two years ago. People use AI tools to be hugely more productive; there’s incredible demand for more software. In 5–10 years, is it more jobs or fewer? Unclear. There will be massive displacement; maybe people find new, interesting, remunerative work.

Interviewer: How big is the displacement?

Sam Altman: Someone told me the historical average is about 50% of jobs significantly change every 75 years. My controversial take: this will be a punctuated equilibrium—lots happens in a short period. Zoomed out, it may be less total turnover than we think.

Interviewer: Last industrial revolution brought revolution and world wars. Will we see that?

Sam Altman: My instinct: the world is richer now; we can absorb more change faster. Jobs aren’t just about money; there’s meaning and community. Society is already in a bad place there. I’ve been pleasantly surprised by people’s ability to adapt quickly to big changes—COVID was an example. AI won’t be that abrupt.

Interviewer: Downsides you worry about?

Sam Altman: Unknown unknowns. If it’s a downside we can be confident about—like models getting very good at bio and potentially helping design biological weapons—we’re thinking hard about mitigation. The unknowns worry me more.

A silly but striking example: LLMs have a certain style—rhythm, diction, maybe overuse of m-dashes. Real people have picked that up. Enough people talking to the same model causes societal-scale behavior change. I didn’t think ChatGPT would make people use more m-dashes, but here we are—it shows unknown unknowns in a brave new world.

Interviewer: Considering technology changes human behavior in unpredictable ways, why shouldn’t the internal moral framework be totally transparent? I think this is a religion—something we assume is more powerful than people and to which we look for guidance. The beauty of religions is they have a transparent catechism.

Sam Altman: We try to do that with the model spec—so you can see how we intend the model to behave. Before that, people fairly said, “I don’t know what the model is trying to do—is this a bug or intended?” We write a long document about when we’ll do X, show Y, or refuse Z because people need to know.

Interviewer: Where can people find a hard answer to your preferences as a company—the ones transmitted to the globe?

Sam Altman: Our model spec is the answer, and it’ll become more detailed over time. Different countries, different laws—it won’t work the same way everywhere, but that’s why the document exists and will grow.

Interviewer: Deepfakes: will this make it impossible to discern reality from fantasy, requiring biometrics and eliminating privacy?

Sam Altman: We don’t need or should require biometrics to use the technology. You should be able to use ChatGPT from any computer. People are quickly learning that realistic calls or images can be fake; you have to verify. Society is resilient; we’ll adapt.

I suspect we’ll see things like cryptographically signed messages for presidents or other officials. Families might have rotating code words for crisis situations. People will, by default, not trust convincing-looking media and will build new mechanisms to verify authenticity.

Interviewer: But won’t that require biometrics—especially for everyday e-commerce and banking?

Sam Altman: I hope biometrics don’t become mandatory. There are privacy-preserving biometric approaches I like more than centralized data collection, but I don’t think you should have to provide biometrics to fly or to bank. I might personally prefer a fingerprint scan for a Bitcoin wallet over giving lots of information to a bank—but that should be my decision, not a mandate.

Interviewer: I appreciate it. Thank you, Sam.

Sam Altman: Thank you.

This is a Guest Post from our friends over at WLTReport.